English ivy, Hedera helix, and Multiflora rose, Rosa multiflora, are but two of the Mid Atlantic’s natural area invaders. Invasive species spread rapidly uncontrolled by natural predators or diseases thereby out competing local, native flora. The result is a reduction of plant species and eventually animal species. Occasionally, these plants can form “biological deserts” or mono-cultures.

English ivy, Hedera helix, and Multiflora rose, Rosa multiflora, are but two of the Mid Atlantic’s natural area invaders. Invasive species spread rapidly uncontrolled by natural predators or diseases thereby out competing local, native flora. The result is a reduction of plant species and eventually animal species. Occasionally, these plants can form “biological deserts” or mono-cultures.The pathways for introduction vary from direct human transportation and cultivation to hidden hitch-hikers found in packing materials and ballast water. The speed of international trade and the ease by which resources from around the world travel has significantly increased the flow of species from their natural self- sustaining environments to new ecosystems around the world.

The general public is at best only partially aware of the issues of invasive species. The complexity of the invasive species discourse requires understandings from the fields of history, geography, botany, biology ecology, meteorology, agronomy, agriculture, horticulture, architecture, art, politics, economics, and law. This list is in not complete.

‘Invasive’, ‘alien’, ‘exotic’ are words which may be heard with pejorative meanings which complicate the public discourse. Current political debates color subliminal interpretations; End goals and agenda may lead to conflict: Native only, free market, and property rights are but a few intersections of contention.

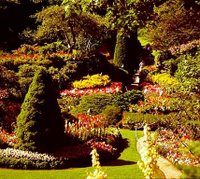

Gardens from Edinburgh, Hampton Court Palace, Butchert Gardens, and Inverewe Gardens are powerful, seductive examples of a great garden type and provide a brief sample of gardening design and desire. The juxtaposing of form, texture and color are all primary features of a modern American garden. Because of ease of travel, and of low transportation costs, any plant may be secured to fill specific design challenges or fancy. The European Age of Exploration brought an explosion of interest in plant types which went far beyond basic medicinal, food or commercial needs. Plant collecting and speculative acquisition projects fuelled western passions for new and interesting plants.

Gardens from Edinburgh, Hampton Court Palace, Butchert Gardens, and Inverewe Gardens are powerful, seductive examples of a great garden type and provide a brief sample of gardening design and desire. The juxtaposing of form, texture and color are all primary features of a modern American garden. Because of ease of travel, and of low transportation costs, any plant may be secured to fill specific design challenges or fancy. The European Age of Exploration brought an explosion of interest in plant types which went far beyond basic medicinal, food or commercial needs. Plant collecting and speculative acquisition projects fuelled western passions for new and interesting plants. One effect of consumerism today is the need to buy the newest or latest of a type. This consumer drive is found in commodities such as new cars and extends into the fashion industry of which gardening is a subset. Historic western agricultural and horticultural concepts are  incorporated in present garden traditions. Western hardening practices stretching over 1000 years are deeply imbedded in the public perception of beauty, and therefore, “correctness” of design.

incorporated in present garden traditions. Western hardening practices stretching over 1000 years are deeply imbedded in the public perception of beauty, and therefore, “correctness” of design.

The urge to find the newest or acquire the latest market offering is one of many pathways for the introduction of invasive species. The market for “new”, starts the process of observation, trial, culling and selection. The widespread importation of plant species can include the unintended consequence of disease or animal introduction.

Gardens have been and are used to signal authority and power. Landscapes send strong messages of authority and domination. A message of control is imparted from grand landscape presentations; those who control nature, surely controls you. The ability to alter and re-form nature powerfully conveys messages to the beholders.

Well tended and manicured edges are methods of control and require the cooperation of specially selected compliant, usually very easy-to-propagate species. The nature of horticultural selection and the needs of some landscape solutions are predisposed towards choosing potentially invasive species.

Natural landscapes which from a distance seem to limit diversity impart a sense of serenity, peace, and tranquility. Too much clutter creates a disturbing image; landscape prescriptions tend to limited species palette. The need for security is most likely hard-wired into mankind, who clears the immediate area at an exit by reducing the species palette to an absolute minimum. Lawns consisting of one species are an example of a security solution which tends in turn impart feelings of serenity, security, and success.

Present landscape solutions address the public’s need for security and accepted current standards of beauty by reducing species diversity, controlling plant growth through cultivar selection. The resulting plant palate may contain plants which are chosen for reasons of hardiness (cold, heat, humid conditions), easy reproduction (speed, success rate, cost), large growing range, and botanical competitiveness. These same criteria are hall-marks of invasive species.

The public right to plant in a personally satisfying manner collides with the need to protect diverse, self-sustaining ecosystems which filter water and clean air and protect biological diversity. The long term responsibility of government to enforce standards to maintain property values and public safety is off set by short term attitudes and tastes. Adding to the invasive discussion are property rights issues, such as zoning, which are layered with the force of centuries, and spiced with current misunderstandings and misperceptions.

In addition there is an intuited presumption that planting “native” is the answer to all or most horticultural challenges. The definition of native and its problems notwithstanding, going native does not in all cases reduce care and maintenance, guarantee survival, or offer short term availability and cost benefits.

Invasive plant species address near term landscape goals for cost adaptability and maintenance. The result of the use of these species which are aggressive and can escape the garden can be the creation of monocultures. Mono cultures or biological deserts contain one species which out-competes all other species. Further, monocultures provide little or no resources for the previously existing ecosystem. Many invasive species are not fed on by existing insect populations the decline of which can reduce bird populations and therefore the overall diversity needed for a self-sustaining ecosystem.

The unintended consequence to eastern woodland edges of the introduction of the Bradford pear, Pyrus calleryana, is substantial. The public is entranced by the white-flowered beauty that most consider natural early in the spring in the mid-Atlantic urban areas. The hybrid off-spring of Bradford pears fill already disturbed former

The unintended consequence to eastern woodland edges of the introduction of the Bradford pear, Pyrus calleryana, is substantial. The public is entranced by the white-flowered beauty that most consider natural early in the spring in the mid-Atlantic urban areas. The hybrid off-spring of Bradford pears fill already disturbed former  farmland which is in the process of returning to some level of a “natural” state though probably not a self replicating ecosystem given the limited area and biological diversity. In addition, long term exposure to the tree in urban garden settings have convinced both the horticultural industry and the gardening public that this is a “bad” garden plant which fails to live up to current minimal expectations as a ornamental specimen choice. The short-lived nature combined with a proclivity to self destruct in wind and ice storms is not yet realized by all agencies local government.

farmland which is in the process of returning to some level of a “natural” state though probably not a self replicating ecosystem given the limited area and biological diversity. In addition, long term exposure to the tree in urban garden settings have convinced both the horticultural industry and the gardening public that this is a “bad” garden plant which fails to live up to current minimal expectations as a ornamental specimen choice. The short-lived nature combined with a proclivity to self destruct in wind and ice storms is not yet realized by all agencies local government.

Local government propagates regulations to enforce development standards. Governments assisting citizens to make informed plant choices through research grants, which address specific needs, such as: erosion (Kudzu), urban street tree hybridization (Bradford Pears) and transportation (Crown Vetch).

In the mid-Atlantic this list may contain Norway maples, Acer platanoides, Japanese barberry, Berberis thunbergii, burning bush, Euonymus elatus, and English ivy, Hedera helix. Given this list, many growers will happily comply and provide these plants.

The three levels of governments differing positions present a tension in the market place and a challenge to natural area land managers. While strategic management plans are in place at the federal level, the states are grappling with agricultural weed laws and environmental and recreational needs, and recognition through the creation of State Invasive Species Councils. Local governments which tend to deal with immediate needs are constrained by limitations on their authority, by limited available funds to create management plans, and by direct constituent demands.

Creative use of the confusion among government agencies can be helpful to both the desires invasive species issue community and the private interest needs. The cross purpose of short term land use and long term environmental repair can result in a positive win for both sides. The removal of the invasive species from the above-pictured site allowed the client to obtain the views of his commercial investment; the retention of the native trees gave the community a sense of woodland setting softening the edge between the hard commercial building and the passer-bys.

This year a renowned national company famous for its depiction and stories of earth is selling a small tree from Australia in the United States, Wollemi nobilis. This species is endangered and was thought lost, but through modern horticultural techniques small clones have been produced. The original stand is protected and the question now becomes one of ethics. Is it alright to propagate species and move them among the continents in order to assure their survival? Should mankind encourage the propagation and movement of plants from around the world? Who decides which species can move and which are confined to their “native” area.

1 comment:

Welcome to the blog-o-sphere! I look forward to many enlightening and thoughtful posts.

On our own blog: http://washingtongardener.blogspot.com/ - we just did a story on 'invasives' of a different kind - coyotes coming (back) into urban territories. In this case, we might well ask: WHO is the invasive?

The topic of invasive plants is a complicated one and has so much emotional baggage attached to it -- my hope is just that folks can remain rational when discussing these topics on your blog.

Post a Comment